… to run “as dim eyed animals do, towards any glittering object, were it but a scoured tankard, and mistake it for a solar luminary” …Memoirs of the Life of Scott – London and Westminster Review 1838 – Thomas Carlyle

There is something extremely appealing about public house drinkware. Even an item that has been maimed and repurposed like this once-tankard are a comforting joy when held in hand and raised ritualistically to the drinker’s lips. This vessel is certainly enigmatic in many ways, from the material it’s made from to its exact provenance, it asks more questions than it can answer. Much like a lot of our public house and brewing history it is possible to find out some information from records and writeups but sadly, much is also down to half-educated guess work and assumption. But there are some clues to its past be found on the piece itself, which at least answer some of the more basic questions it poses ...

-o-

This tumblerised tankard carries the word ‘1/2 Pint’ as well as the term ‘Masonoid Silver.’ It has a rubbed Edwardian stamp showing a crown flanked by a very faint later E plus an R, with the Uniform Verification Number 6 below the crown denoting it was verified in Birmingham, where it was manufactured. There is also a tiny M to the right of the verification mark whose purpose is unclear although it may reflect a date, but that Edwardian stamp puts its manufacturing firmly prior to 1910 and probably post 1902. At some point someone has removed the handle, which would have been rounded and C-shaped, and the surface is also covered in roughish scratches which means the engraved name showing the words ‘International Bar’ in, and on, a belt and buckle design is almost obliterated. Perhaps it had become damaged in use and repurposed, but as the heavier and deeper gouges are very much focussed on the engraved bar name in order to obliterate it, it would appear that the tankard may have been taken from the bar by somebody for a specific purpose, which has become lost to history.

The belt and buckle device is in fact a 'garter' and appears to have originated from the emblem of The Most Noble Order of the Garter, with the garter in question being a part of a knight's wardrobe for securing parts of the armour together or to the body. This motif turns up in many logos, decorations, and trademarks in the late 19th and early 20th century, perhaps as a way of adding an air of ostentation to a brand, company or object without it being actually connected to the order.

Masonoid Silver was a durable, bright metal alloy developed by Samuel Mason in Birmingham around or prior to 1887, when it first starts to appear under that name in publications. It was originally available in two colours, one as a replacement for silver or silver plate and another as a replacement for copper or brass. It was possibly a type of Nickel Silver, which contains mostly copper with nickel and zinc, but more was more likely similar to an early version of a more expensive alloy patented as Monel in 1906 and composed mostly of nickel with less copper than Nickel Silver and with small amounts of iron, manganese, carbon and other elements. Masonoid was used for many products, particularly those that revolve around the drinks trade such as beer engines and taps, as well as bicycle parts and other applications. The company went through a number of name changes and partnerships, such as The Masonoid Silver and Midland Rolling Mills in 1898, before disappearing from historical mentions by the end of the second decade of the twentieth century and is now only remembered in objects like this.

-o-

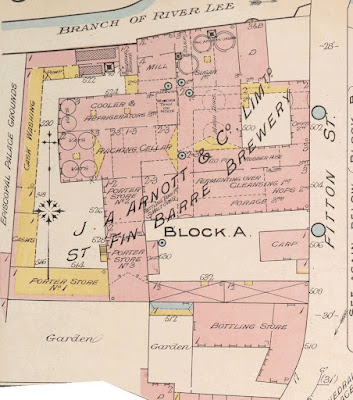

It is tricky to ascertain exactly which International Bar this tankard was made for as there appears to have been at least three public houses bearing that name on the island in the very early 1900s. There are newspaper mentions that reference an International Bar on Market Street in Derry, which was operating around the same time and had a reopening in 1907, which certainly ties in with the date of the tankard. There also appears to have been a pub of the same name in Newtownards and perhaps one in Belfast. It is quite possible that this object relates to any of those bars but it is equally conceivable that the tankard came from The International Bar in Dublin. (Especially given that it was discovered in a shop that specialises in house clearances from the Dublin area.) This bar still exists and appears to have been quite a salubrious spot since the very late 1890s, so it would certainly suit as an establishment that had commissioned its own personalised tankards, but sadly there is no recorded proof of this in the common sources.

The Dublin based International Bar began its beverage selling life on a slightly smaller scale than its current footprint, as it was originally focussed on the side of the building that sits on 8 St. Andrew Street, although with some frontage also on to Wicklow Street as it sat on that corner. As far back as 1827 a Mrs. B Cavenagh (also spelled Kavanagh) had a grocery, tea, wine and spirit warehouse on the site, and a possibly related James Kavanagh of the same address was declared insolvent in 1838, having let the license go into arrears the previous year and the building go into a state of disrepair, so the lease was up for sale at that point. The premises was taken over by a John Hoyne in that year and repairs were made to the building before he was granted a publican’s license, although it was opposed by some local people on the grounds that there were already 19 public houses on nearby Exchequer Street alone! A wonderfully, Joycean named person called Stephen Pidgeon applied for a license for the premises in 1839 and 1840, before it was taken on by John Dunne in 1843. Mr. Dunne appears to have ran it as a spirit grocers until his death in 1880, and by 1885 it was being operated by a John Cox. In 1887 Michael O’ Donohoe, a Cavan native, applied for a license to retail alcohol at 8 St. Andrew Street and was also leasing the 23 Wicklow Street building around the corner by 1892. (That address also appears to have been occupied by a tailor’s shop and then a jeweller and clockmaker, which overlap slightly with the O’Donohoe lease dates, but that might have been on the upper levels of the building or it may have been sublet.) In 1897 Mr. O’Donohoe applied for a new licence to sell alcohol on that attached building on Wicklow Street, it now being an extension of his original business. But big changes were afoot …

On Friday the 5th of August 1898 the International Bar, as it was then named and as it appears today, was opened as a completely new build on the two sites acquired by Mr. O’ Donohoe. A newspaper advertisement from this time reads thus:

THE INTERNATIONAL

ST. ANDREW ST. & WICKLOW ST.

___

M. O’DONOHOE

Begs to inform his Friends and the Public that his New Premises,

THE INTERNATIONAL BAR,

WILL BE OPENED

ON

NEXT FRIDAY, the 5th inst.

This Establishment has been fitted up throughout with the Electric Light, generated on the premises by powerful electric generator, worked gas engine of Crossley Bros, Warrington, and has already been pronounced by competent judges one of the finest of its class to be found either home or on the Continent.

In point Architectural Design and Beauty it stands second none. The art decorations and ornamentation are of the most modern and up-to-date style. The plans were designed by George O’Connor. Esq, MRIAI, and the building was carried out under his personal supervision. The Sanitary arrangements are of the most Modern Type, and ate complete In every respect.

The International has been built and fitted up regardless of expense.

It is intended it should occupy a foremost place amongst the Establishment class in this city, where Gentlemen from every part the world will find every accommodation and their requirements catered for in the best manner under the personal supervision of the Proprietor.

The Refreshments, both Home and Foreign, will all of the very best manufactured, and no inferior qualities will kept slock.

___

THE BRANDIES, CHAMPAGNES, WHISKIES, AND WINES,

OF ALL KINDS, TOGETHER WITH

ALES. BEERS, PORTER, STOUT, AND MINERALS, &c., &c.,

HAVE BEEN SUPPLIED BY THE LEADING MANUFACTURERS,

And will found fully Matured, and in the finest. Condition.

The CIGARS, &c., are all selected from the Best Brands.

Mr. O’D. Cordially Invites the Public to Visit his ESTABLISHMENT,

and he guarantees them every attention and courtesy.

___

LUNCHEONS OFF JOINTS A SPECIALITY.

___

NOTE ...

THE INTERNATIONAL

ST. ANDREW AND WICKLOW STREET

M. O’DONOHOE, Proprietor

Another advertisement from later in the month is of a similar vein and includes the following paragraph:

The proprietor begs to inform his numerous friends and customers and the public generally that this magnificent establishment - the finest in the city - is now in full swing and worthy the attention of connoisseurs.

THE BEST OF EVERYTHING SUPPLIED

___

J.J. & SON'S WHISKIES,

GUINNESS'S STOUT,

BASS'S ALE,

Etc, Etc, Etc

It is certainly a fine building of excellent design and sits very handsomely to this day on that site. No expense appears to have been spared with its build and fit out so it is hardly surprising that shiny new tankards may have been purchased for the premises a few years later, engraved with the bars name.

Mr. O’Donohoe died in October 1904, and his funeral was attended by most of the other licensed traders in Dublin, a sign surely of how well he was thought of by his peers.

-o-

It could be argued that this object is more connected to beer serving and public houses than with actual Irish brewing history, but both are of course intrinsically linked so it is impossible to have a conversation about one without involving the other.

Irish pubs have always been an essential part of Irish brewery history, albeit with their former fondness for English-brewed Bass et al., and their present dalliances with foreign lager brands – although at least, as with an iteration of Bass at one time, many are brewed in Irish breweries.

The Irish brewing industry should - rightly - evolve, improve, and embrace the new, but Ireland has lost most of its breweries over the last couple of centuries. They became hollowed out brands within the portfolios of drink corporations, detached and rebooted as one-off, one-dimensional beers, with their history discarded, disfigured, and diluted. But many of the public houses that served the beer from lost breweries still exist in one form or another, and they are entangled in our brewing provenance and 'heritage,' to use an overused word. Many of the public houses of Ireland have now become the historical repositories of our relatively recent beer-laded past, as they have become aesthetics-driven exhibitions of artefacts and ephemera from that now-lost era, even though they lack perhaps the knowledge, the interest, or the want to communicate any of this history to their customers. Understandably, many focus on their own history – sometimes scribbled on the back of a beer mat over a few pints after closing time it appears – but not on the actual libations they pulled and poured over previous decades or centuries.

A cynic might say that there is little point in trying to communicate history of any type to those who don’t care, but in many cases it is how that information is communicated is the key. Irish bars are certainly good at storytelling, but for today's audience they need something more than just words, they need something tangible and ‘real,’ a touchable connection to our brewing past that will engage the customer and stimulate some conversation. It might be that framed letterhead from Mountjoy Brewery, or the beer label on the wall for D’Arcy’s Stout. It could be an old, embossed bottle from a famous Sligo brewhouse sitting on a shelf, or a price list from a Kilkenny brewery listing all of its beers.

It might even be a worn and damaged tankard that may in the past have been filled with a half pint of plain porter or a pale ale in a newly built bar in a busy city.

These stories need telling, before all of our history is completely worn away …

Liam K

Please note, all written content and the research involved in publishing it here is my own unless otherwise stated and cannot be reproduced elsewhere without permission, full credit to its sources, and a link back to this post. The photograph and tankard itself are the authors own and the image cannot be used elsewhere without the author's permission. Newspaper research was thanks to The British Newspaper Archive. DO NOT STEAL THIS CONTENT!