Cat skidded along the counter, its paws losing traction on the shiny surface as it tried to escape the flick of a cloth from the Her, knocking a bottle containing the dregs of the dark bitter stuff over and leaving it bouncing and spinning on the cold marble – a small trail of froth and stickiness in its wake. It was usually less clumsy, but the Her had surprised Cat when she had come up from the Underneath and caught Cat staring curiously at the newly delivered ham that she had left hanging from a hook above the counter while she relayed a message to the Him.

'That bloody cat!'

Cat stopped running when it was out of harm’s way and slinked off towards the other end of the bar, where it sat down and began cleaning itself of the small drops of liquid that had landed on its calico coat while the Her cleaned up the mess on the bar, all the while muttering and throwing annoyed looks at Cat, who stopped its preening every few moments to make sure that the Her was still far enough away not to hit it with anything. From down below in the Underneath came the sounds of clinking and the grunts and groans of the Him and - being by default a curious creature - Cat jumped down from the bar and padded down the worn timber steps, careful to avoid the Her as she headed towards the kitchen with the ham on her shoulder.

Cat sat on a step halfway down and looked at what was happening in the place that it saw as its play- or more accurately hunting-ground. The Him was down here wrestling with a large, heavy wooden barrel that had arrived earlier, while the Himling - who looked like a younger and less rotund version of the Him - stood with his finger rooting in his ear and a glazed look in his eyes.

'Jaysus, don’t stand there like a gobdaw, help me with this will ya?'

This was a common sight for Cat, with the Him doing the work while the Himling just stood around until forced to move and do something by the shoutings of the Him. Cat didn’t really know what was being said but it was no stranger to the tone being used when he occasionally got under the Him’s feet or just generally got too close.

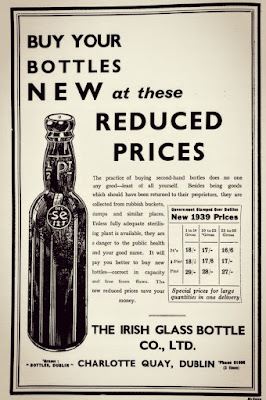

A similar scene had played out the previous day with Him shouting at the Himling above the dull clinking of glass as the Himling filled a big round tub with the old bottles that had sat in crates down here for the last while. Next the Himling donned a sacking apron and added some cold water from a tap on the side wall to the tub before topping it up with steaming water from a bucket to which he had added some spoons out of a bag labelled ‘Soda Crystals’ - not that Cat knew what the bag contained as it could not read of course. All the while the Him was shouting at the Himling to hurry up as Cat watched on from its perch on a broad shelf filled with dusty paraphernalia. The Himling then got a brush-like thing with loads of bristles and proceeded to push and twist it around inside the bottles one by one, checking them by holding up towards the bare lightbulb that hung from the ceiling, until all of them had been scrubbed. Next the Himling scraped off the old label from the outside of the bottles and rinsed them all before setting them upside-down in a rack in order to drain and dry.

Today the bottles were still sitting there and Cat came cautiously down the stairs to find its perch once again and watch the ritual he had seen happen many times before, pausing just briefly to distractedly push with its paw a few of the wooden corks that were floating in hot water near to a very low stool.

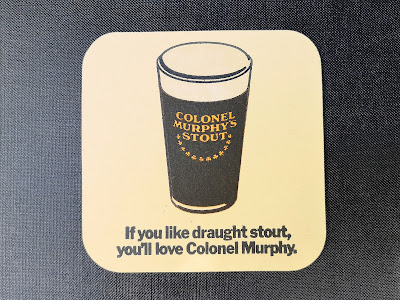

Him and the Himling ignored Cat, as they were currently rolling the barrel back and forth on the cold slabs, which they did for a short while before placing it on its side - and with some effort - onto a low wooden stand. Cat watched as the Him loosened something with a hiss on what was now the top of the barrel before picking up a brass tap with a perforated tube on one end and a wooden mallet, he then wrapped some folded newspaper around the end of the tap and positioned it at the bung at the bottom of what had been the round top of the barrel, before striking the tap end a few times to drive the bung into the barrel followed by the tapered end, with the paper wrapping forming a tight seal. Cat had watched this process on occasion before and sometimes a jet of black liquid would shoot out of the barrel and hit the Him square in the face, causing a string of words to be uttered that would make the Her come down the steps and tell the Him to shut up as there were gentlemen and ladies present in the Up Above that day. But no accidents happened this day, so the Him got a mug and poured some liquid into it from the now secured tap, tasting it before grunting approvingly.

Cat jumped down on the newly tapped barrel and watched as the Him then took the Contraption with its rectangular bowl and 4 pipes and placed it under the tap and proceeded to fill the bowl with black liquid from the tap that was now in the barrel. The Himling then sucked the ends of each of the four pipes to get the liquid to flow into the four bottles he had just positioned under each of the pipes, spitting mouthfuls of black liquid back into the bowl that was being filled. The Himling would take the empty bottles he had cleaned the previous day from their rack at one side of the Contraption and once filled by one of the four tubes, he'd put them on the ground on the opposite side and put another bottle under the filling pipe and repeat the process.

'Get off of there!'

The Him had dragged the Mechanism towards the barrel beside where the Himling was leaving the bottles and positioned the bucket of corks beside it, he threw a cork at Cat but missed - Cat just looked at the Him curiously and continued his observations. The Him just sighed and inserted a cork from the bucket into a pull-out section on one side of the top of the Mechanism, he slid that section into place, positioned a bottle on a little plate underneath before pulling down on a long lever that forced the cork into the bottle. He then placed the bottle into a crate and repeated the process, the Him and the Himling working in silence apart from the quiet gurgle of the dark liquid in the Contraption and the dull clunk of the lever in action of the Mechanism.

'Oh hello pussycat!'

The Herling had arrived home from wherever she went during the day, and Cat liked the Herling as she gave it little treats of meaty scraps and hard rubs behind the ear, both of which pleased Cat. But today the Herling went to where the Him and the Himling were sitting on the low stools in front of their machines, picked up a crate of filled bottles and carried them over to a table near the back of the Underneath. She opened a brown envelope that was sitting on the table and took out a thick bundle of oval, beige labels tied up with string. She cut the string and left the pile beside the crate of bottles. Then she got a small bowl to which she added a spoonful of white powder from a bag with the word ‘Flour’ written upon it – not that Cat knew that - and mixed them together. Then she used a small paint brush to put some of the mixture on the back of the label and affixed it neatly to a bottle, then she too – like the Him and the Himling – fell into the non-musical rhythm of repetitive work, with the air smelling of hot corks, spilled stout and floury paste, tinged with the greasy metal smell from the Mechanism and the musty odour of the Underneath itself.

Cat wasn’t happy at being ignored, it jumped up beside the Herling and sniffed at the mixture in the bowl before butting her elbow with its head, almost making the Herling drop a bottle.

'Silly puss! Don’t do that.'

The Herling picked up Cat and put her back up on the barrel that was almost empty, much to the annoyance and mutterings of the Him. Soon the tap began to gurgle and the tray in the Contraption that the bottles were being filled from was empty. When he had finished corking the bottles, the Him pried out the brass tap from the end of the barrel and used the mallet to beat back a round piece of timber into the hole to seal the cask tight again. Cat had to jump quickly off the barrel as the Him and the Himling lifted the barrel back upright and set it near a trapdoor to the Outdoors where Cat knew these barrels appeared and disappeared from regularly.

The Herling was finished putting the beige round labels with writing on them on the bottles and the Him and the Himling took the crates, each holding two dozen bottles, and stacked them at the end of the cellar six high, where Cat knew they would sit for a third of a Moon’s Time before being brought a crate at a time up into the Up Above where the people came and the corks were removed from the bottles with a long handled machine that was attached to the bar, before being poured into a glass in exchange for Round Metal Things that clinked as they were tossed into a drawer underneath the counter.

Cat yawned and stretched, then it sniffed the air for any smell of the Grey Squeakers that sometimes wandered into the Underneath, as it was his job to catch, play with, and crunch them. There was no scent of them today but it would return by its secret way later that night to check again, on its nightly patrol of the Underneath.

Just then the Herling appeared beside Cat and picked it up.

'Come on puss, up we go.'

Cat let himself be carried up the stairs purring contently, with Him and the Himling following behind after having cleaned the Contraption, putting away the Mechanism and mopping the slabs.

When everyone was upstairs the Him closed the door into the Underneath, and they headed towards the kitchen and the smell of cooking ham. The Him stopped briefly to gather four glasses before opening two bottles of stout and two minerals. They had an hour to eat, drink and rest before the doors would be opened and more bottles poured for their thirsty patrons.

And as ever, Cat would watch over all proceedings …

Liam K

|

| 'Contraption' |

|

| 'Mechanism' |

[The bottling routine described here is adapted from notes regarding the procedure in the 1950s in “A bottle of Guinness Please” by David Hughes, and supplemented by passages in “3 Score and 10 – A Great Leap” by Cartan Finegan plus parts of Flann O’Brien’s “Myles Away from Dublin.”]

(Cat Photo via rollingroscoe on morguefile.com, and the Contraption and Mechanism photos were taken by the author from the public house display in Carlow County Museum.)