[Warning: Contains violent descriptions]

He stirs …

He hears the front door closing and being latched as the last of the stragglers make their way on unsteady feet into the night, then the creak of the worn oak steps as the widow makes her way slowly upstairs to her bedroom. Muffled sounds carry through the layers of timber as she slowly undresses and her now lonely bed takes her sparse weight, a sigh drifting down to his all-hearing ears. His eyes shine green in the darkness down below as he stands on the cold stone floor in the place where he lives in the shadows, beneath the floorboards where the people drank, danced and talked just a short while ago.

He creeps silently from his hiding place, past the crates of bottles that line the oak shelves of the cellar, his eyes well accustomed to the darkness as he stretches his limbs, his joints cracking like the breaking of a rodent’s bones. The steps are as cold and damp as his skin as he crawls slowly up them to the heavy trapdoor and uses his back to push it open, his nose sniffing the remnants of food and stale beer. He eases his way from his hiding place and slowly lets the door sit silently back into it place, a task that takes almost all his strength. Now he stands as upright as his hunched back will allow, his squat body glowing palely in the light from the moon that shines through the window, reflected off the wet street outside.

He is a thing of legend, mocked and maligned by the questionable works of bewildered writers over the centuries. He and his solitary people are known by many names but in this dark and wet land and in his current form he is known as a Cluricaun – at least in modern speech – a creature who hides in cellars and is rarely seen. On his withered body he wears just a ragged apron he found that smells of sour beer, mould and the rats that he eats when he can catch them – their guts and blood soaking into the ancient leather-like material.

In the darkness he starts to search for the scraps of food that may have fallen on to the wooden floor and have been missed by the widow’s brush. He walks with a strange lumbering gait, pivoting at the hips, his big feet splaying widely, but silent as he searches in the forgotten corners of the room. He has two pockets in his apron, one he fills with the few crumbs he finds that will make a welcome change from his usual fare, and in the other he places any spent, discarded matches he finds wedged between the floorboards or stuck under the skirting boards. He stops as he hears a sound from up the stairs as the widow turns in her sleep and her bed creaks, his over-large head cocked at an angle and his big, pointed ears listening carefully for further movement, but nothing else stirs the silence.

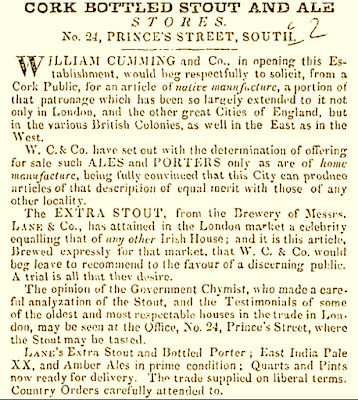

He dares not go behind the bar in case he hits against the bottles or glasses in his clumsy way, although he was not always so. He is beyond ancient now and some of his bones and joints have seized or fused together causing him to walk in such an ungainly fashion. Finished with his search he returns to the trapdoor and with difficulty eases it gently open, and once again balances it on his humped back as he lets it close quietly and he heads back down the steps to his lair. The few tiny pieces of bread he found upstairs are soon eaten and his ever-present thirst rises - his need for drink urgent and greedy. He goes to the part of the cellar where the barrels labelled ‘XX Stout’ are kept and removes an old piece of twine from around his neck, on which is tied his most important possession. It is a long narrow tool, pointed and with curved threads at one end, and a handle on the other – a gimlet. He pushes the tool into the hard timber of the barrel and twists it from side to side before turning it clockwise and letting the threads find purchase as the tool drags itself into the oak until it pushes through the stave and spins freely. He removes the tool and quickly puts his mouth to the spurt of black frothy liquid that erupts from the hole. He drinks enough to sate his thirst but not so much to be noticed by anyone, and when he finishes he removes three matches from his pocket and jams them in the hole, letting the liquid swell the wood and block the small opening he made. He wipes his mouth with the back of his hand and thinks about how much he loves the dark liquid that arrives weekly into his lair. Drinking it makes him feel more content and fuller than the rats and morsels of food could ever do. He creeps back into the darkness behind the old furniture and crates that are stacked in a jumble in the farthest reaches of the cellar and lays down on a pile of damp sacks. This is the place he goes to when the widow descends the steps to put the strong black liquid into the bottles that she serves to those who visit the room upstairs. He watches her from the darkest recesses of this place when she corks each bottle and puts them into crates, and she never misses the liquid he removes so carefully.

He dozes now and remembers a past life when he lived in secrecy too but above ground instead of below, when he was nimbler, younger, and stronger. A time where he roamed the streets and fields of this place and hoarded the shiny trinkets he took from those who would not miss them, and kept them safe in his secret hiding place. But over time and before he recognised it happening, he had gotten old and careless. He forgot where he stored his treasures and, unable to move quickly and be unseen by the bigger folk, he retreated as others of his kind had to the dark safe spaces below the surface where he could hide more easily, slowly weakening and decaying. He knows also that one day soon he will need to crawl into the hole he has prepared under one of the slabs in this dark place, remaining truly hidden as he turns back into the earth from which he came.

He is brought back to the present by a noise from upstairs, a series of heavy thumps and muted cracks followed by a low moan. He cocks his ear to the sound and hears the whimpering groan again. Slowly and carefully he ascends the steps, once again raising the trapdoor, and listens. He hears the moan again and he eases his way out of the cellar, carefully closing the heavy trapdoor behind him, and slowly peers around the corner of the bar.

The widow is lying at the foot of the stairs, a glass tumbler rocking on the floor not far from her outstretched hand. She is crying softly now, and even from where he is half hidden he can see that her old limbs are twisted at impossible angles. One slipper is on her foot while the other is halfway up the stairs. He wobbles over to her not knowing what to do, and her eyes open wide when she sees him approach and she mumbles a prayer through her broken jaw. Her body is trembling with pain and fear as he stands over her. He has seen the same thing happen to the rats that are caught in the traps in the cellar, as they writhe and squeal in the dark, awaiting death.

He pauses and stares at her for a short time until he steels his resolve, knowing what he has to do. He takes his gimlet from around his neck and kneels with some difficulty beside her, before forcing the tool into the widow’s ear and upwards until he feels the bone give way and a sharp crack. Her body goes still and the low sounds she had been making stop. He removes his trusty little tool and is about to wipe it on his apron when he stops, and for no reason he can think of, licks the blood from it instead. It tastes a little like a rat’s blood but richer and stronger, and there is something else there, as if some of the widow’s very soul and essence was contained within her lifeblood. His eyes open wider and he licks his lips, then he puts his mouth to the widow's ear and sucks at the blood that is trickling out in a slow stream as her heart pumps for the very last time.

When he finishes, he stands up and stretches out his curved back, he twists his joints and feels them freer that they have been in many a decade, or perhaps centuries, as he forgot his age many years ago. He feels a great change happening, his limbs no longer ache and he is fuller and healthier than he has ever been from drinking the black liquid from the barrels. He looks at the widow’s body and feels a little sadness for what he has done, but she would have died anyway, he just ended her pain quickly. So what if he had received an unexpected reward for his good deed?

Someone would find the widow’s body in the morning and know that she had fallen down the stairs. There was no trace of his act of mercy to be seen and no sign of blood there either. He heads back down to his lair, easily opening the trapdoor and letting it slam behind him as he almost dances down the steps quite full of life. Perhaps he should venture outside, find more suitable clothing, and look for his lost treasure? Yes, that seemed like a great idea. Maybe he will find a new and more suitable place to live, although he does still love that black liquid – stout – that arrives here in those barrels so maybe he should stay close by after all?

But he now knows what he needs to do to keep feeling this strong, and that he will have to supplement the barrel theft with something else - something redder, richer, and stickier. He also knows of course where that precious liquid can be found, and that new people will come to this place soon to replace the widow. Then they will bottle the black stuff in the barrels and give it to the too-loud people who come through the door and sit on the stools at the bar. Some of these people will wander home very late at night - on their own, and full of stout, down lonely, darkened streets ...

There will be new sources of his vitality he thinks, his eyes burning bright red from within in the darkness of the cellar.

All written content here is my own and cannot be reproduced elsewhere without permission, full credit, and a link back to this post. Images are also the author's own.