In Ireland the pint bottle has achieved a semi-legendary status and is remarked upon and reminisced about it in equal measure as it slowly disappears from the fridges and shelves of the bars in this country. There are still many who appreciate its legacy, history and heritage, even if much of these elements are misunderstood, and there are those who enjoy and savour the taste and flavour of a beer poured the ‘proper’ way from a pint bottle into a ubiquitous flared pilsner glass, or just ‘A Glass’ as it is called in Irish pubs. At this point in time there are just a few beers still available in this Imperial measure and method of serve - the Diageo brands of Guinness, Harp, Smithwicks and Macardles, while Bulmers cider is also offer a pint bottles. These are the last relics of what was a huge industry of the past, where most of the beers consumed on this island were served in pint, half-pint and one-third-of-a-pint bottles, and when bottling companies as well as the publicans themselves bottled huge amounts of the output from Ireland's breweries. There was for sure a trade in draught beer served straight from the cask but this was more limited, and probably more often found, in the busy urban public houses.

So in most of Ireland the bottle was the most common way of drinking beer both at home and in the pub, but our love for the pint bottle is a relatively recent affair, as the half pint version was the most popular way of serving most beers for decades here, and certainly for a long period after the formation of the state in the 1922. It remained so until Draught Guinness and other draught keg beers became popular, and took over the pub beer sales in most of country. So these bottles -especially the smaller size - would have been a familiar sight in pubs, grocery shops and homes throughout Ireland.

Prior to the 1920s there was a mixture of bottle sizes that were known and discussed in the trade by how many of said bottles you could fill from a gallon of beer, so there were ‘12s’, ‘13s’, ‘14s’ and ‘16s’, with the ‘16s’ equating to a half pint (10fl. oz. or 284ml) and the others sizes up to ‘12s’ (13.33 fl.oz or 379ml), and although this latter size were sold as ‘Reputed Pints,’ interestingly there is very little mention of Imperial pint bottles up to this period.*

The newly created government of Ireland finally got around to addressing the issues around bottle sizes a not long after its formation when they published the Intoxicating Liquor (General) Act, 1924, which states the following:

9.—(1) The Minister for Justice may by order prescribe the sizes of the bottles in which any specified intoxicating liquor may be sold, and where any such order is in force it shall not be lawful to sell or supply the intoxicating liquor specified in the order in bottles of any size other than one of the sizes prescribed by the order.

And then in 1925 the following appears in the Intoxicating Liquor (Standardisation of Bottles) No. 1 Order, 1925:

AND WHEREAS it has been deemed expedient to prescribe the sizes of the bottles in which ale, beer, porter and stout may be sold:

NOW I, CAOIMHGHÍN Ó hUIGÍN, Minister for Justice, by virtue of the powers conferred upon me by Section 9 of the Intoxicating Liquor (General) Act, 1924 , and of all other powers enabling me in that behalf, do hereby order and prescribe as follows:—

On and from the 1st day of October, 1925, all ale, beer, porter or stout sold in bottles containing less than one standard quart shall be sold in quarter-pint, half-pint, or pint bottles [...]

This had to be amended on the 30th of December - possibly because the quarter-pint bottle was an error - to read:

(2) On and from the 1st day of January, 1926, all ale, beer, porter or stout sold in bottles containing less than one standard quart shall be sold in bottles containing one-third of a pint [my emphasis], one-half pint, or one pint.

(This piece of legislation was only revoked in 1983, presumably allowing the sale of any size bottle of beer providing the volume was stated on the label and that volume was correct, although this was probably the case anyway thanks to European legislation and regulations from 1977 regarding alcoholic drink volumes.)

This regulations needed to be enforced and further clarification appear to have been needed so we have another piece of legislation added on the 3rd of February 1926 which offered more information in 11 points, the most interesting being:

2. These Regulations shall come into force on the third day of February, 1926.

So a change from the date cited above.

4. The capacity of each bottle shall be defined by a line stamped on the bottle of not less than three-quarters of an inch in length and distant not less than one-and-five-eighth inches nor more than one-and-seven-eighth inches from the brim of the bottle.

This helps us to see why an where the fill lines appear on these bottles.

6. A bottle which is not completely emptied when tilted to an angle of 130 degrees from the vertical shall not be stamped.

This simple piece of wording shows why the sloped ‘shoulders’ on bottles are the shape and size they are!

7. The denomination of a bottle may be indicated by the abbreviated form of " Pt.", " ½ Pt.", or "1/3 Pt." respectively.

Again, we can see this on the bottles shown above.

8. If a maker's or trader's name is stamped on a bottle, it shall be in letters not exceeding one-half the size of the letters indicating the denomination.

On embossed bottles this defines the maxim size the bottler’s name can be appear.

11. In the case of bottles which are in stock or in use for trade on the date when these Regulations come into force, the provisions of Article 8 of these Regulations shall not apply, and the following provisions shall have effect in lieu of the provisions contained in Articles 4 and 5 of these Regulations, that is to say :—

(a) the capacity shall be deemed to be defined by an imaginary line drawn at one and three-quarters inches from the brim of the bottle ;

(b) the allowance for error permissible on verification and inspection shall be, in the case of a pint or half-pint bottle, not more than one-and-a-half drachms in deficiency nor more than one-and-a-half ounces in excess, and in the case of a one-third pint bottle, not more than one drachm in deficiency nor more than three-quarters of an ounce in excess.

Provided that the provisions of this Article shall not have effect after the 31st day of December, 1927, or such later date as may be defined by subsequent Regulations, and that after the 31st day of December, 1927, or such later date, no bottle which has not been verified and stamped pursuant to the provisions of Articles 4, 5 and 8 of these Regulations shall be deemed to be lawfully verified and stamped.

This is a long-winded way of saying that it is permitted to keep using unverified bottles as long as they conform to the legislation regarding volume, and they are destroyed or recycled by the 31st of December 1927 unless new legislation is published - and indeed it was changed on the 7th of January so that said bottles that were stamped or etched according to the legislation could be continued to be used in the trade regardless of their date of manufacturing.

Much of this legislation is tedious and difficult to analyse but Weights and Measures Act of 1928 clarifies much of what had gone before and more importantly gives is some clarity on the mystery of the numbers, letters and writing on the bottles shown here, and most others that are found in the collections of museums and breweriana collectors. It appears it was possible to incorporate verification marks into the manufacturing process of the bottles as part of the mould in which the bottle was formed and this is seen on these examples as ‘DIC’, ‘SE’ and the numbers ‘127.’

We can break these down as follows:

SE stands for ‘Saorstát Eireann’ the Irish translation for the Irish Free State which existed from 1922 until 1937.

The letters ‘DIC’ can appear quite puzzling but its meaning becomes clear if you look at the government body who was in charge of all of this legislation – The Department of Industry and Commerce.

127 is a little trickier but if we read Part 1 section 7 of the above mentioned act - Verification and stamping of bottles during manufacture – we see the following:

The Minister may, if and whenever he thinks fit, grant in respect of any factory in Saorstát Eireann a licence in the prescribed form authorising all bottles to which this Act applies manufactured in such factory to be stamped in the prescribed manner during the process of manufacture with a stamp of verification under the Weights and Measures Acts, 1878 to 1904, as amended by this Act or with an impression derived from such stamp, and a factory in respect of which such a licence has been granted and is in force is in this section referred to as a licensed factory.

Therefore certain large glass bottle manufactures such as the company who produced those shown above – The Irish Glass Bottle Company – could bypass the need to apply individual etched on verification details by getting this licence. So it appears that this number 127 is the licence number given to this factory, which operated in Ringsend in Dublin.

Indeed the act goes on to say:

The methods of verification and stamping of bottles to which this Act applies authorised under this section shall, in respect of such bottles manufactured in a licensed factory, be in substitution for the methods of verification and stamping required or authorised by or under the Principal Act.

The company still needed inspectors from The Department of Industry and Commerce to check batches of bottles and certain fees needed to be paid, but it made the process simpler than that for drinking glasses for example which needed to be individually etched with the year date and the inspector or area number in the presence of said inspector. Other parts of this general legislation alludes to these inspectors being members of Gárda Síochána (The Irish police force), or at least appointed by them.

(The numbers that appear on the bottom of these bottles alongside the obvious initials ‘I. G. B.’ are a little more enigmatic but presumably stand for the mould numbers and variants.)

-o-

Much has been written about the rise and fall of The Irish Glass Bottle Co. but our interests are in how it operated and functioned in the period of our concern - the 1920s. In 1928 an article regarding a visit to the company appeared in The Dublin Leader newspaper:

THE IRISH BOTTLE INDUSTRY

It was a Wexford man, Michael Owens, who in America first invented an alternative to mouth blowing in the making of bottles. A bicycle pump suggested the idea to him. The modern machines that developed out of that simple idea are still called after Owens, and to-day on the premises of the Irish Glass Bottle Co., Ltd., Charlotte Quay, Ringsend, Dublin, there is at work one of the largest and most modern Owens Bottle machines.

These bottle works are in full swing now. When we first visited a bottle factory in Dublin many years ago the Owen machines were things of the future, and it was all mouth blowing; in fact we blew a special bottle ourselves and took it home as a souvenir. A modern bottle factory is in parts a very hot place, as the heat in the furnace registers about 1,300 degrees C. Until some time back coal was the fuel used; now oil has superceded[sic] it, though at any time the factory can go back to coal if desirable. The main raw material is sand which is got from the Sutton-Malahide district, and needless to say the lime used is also a native product.

The furnace is going since November 1st last, for once the extraordinary temperature of about 1,300 is reached you have to keep it up, and so the works are carried on in three shifts of eight hours each, and the furnace never cools. The machine delivers the red-hot bottles in the course of not many seconds and workers take them up with long tongs—when you deal with red-hot bottles you need a long spoon—and place them on a steel belt revolving through another furnace. The latter furnace is 8o feet long and is quite cool at the other end; it takes about six hours for these bottles to travel the 8o feet, and by that time they are cooled. The machine is equal to turning out about 2,000 bottles in an hour.

Many things have occurred with regard to bottles in quite recent times, The tariff on bottles is 33 1/3 %, bottles under five ounces—at the request of this Company—-being admitted free. Our readers can guess the size of a five ounce and under bottle, when they are told that an ordinary beer bottle is ten ounces.

Who pays a tariff and to what extent do various parties pay it ? If a tariff excludes foreign goods and the prices of home goods do not rise, there is obviously nothing to pay; the only change is that the home Country has the whole home-market. There are foreign bottles still coming in from Germany, and from England. The prices of the half pint beer bottles is 20/- per gross and the question as to who pays the tariff is easy seen in this particular case. The imported bottles are now sold at about 15/- per gross, less duty, which practically means that Germans and English pay the tariff. In due time when the outside competitors find that undercutting will not down the Irish factory, they will give up the game and the Saorstát bottle factories will conquer the Saorstát market. The slight advantage which jam, sweets, etc., have, owing to existing taxation, has given a great fillip to jam making and consequentially the bottle industry benefits. One of the great results of any manufacturing industry in a country is the consequential effects on other home industries. Jam making has been very considerably extended in the Saorstat[sic] and the Irish Glass Bottle Company is doing a very big line in glass jars for home manufactured jams.

Some time ago there were a variety of sizes - rather of internal content—of bottles in the stout trade; the capacity of the bottles ranged from twelve up to even seventeen bottles to the gallon. The Government have stopped profiteering in that line and have made it imperative that every stout bottle contains half a pint. There is already—and there must be after a certain date—what we might call a Plimsol mark on the neck of every beer bottle it registers the half-pint contents. At the Base of some of the bottles now being turned out the words “Bottle made in Ireland ” are embossed, and we understand that this will, in due time, appear on all bottles turned out in the factory.

It is only recently—about two years ago—that the manufacture of white bottles and jars has been started. When we were in the factory last, some six years ago, there were no white bottles being made, and we expressed the hope that that development would come in time. It meant new machinery and large capital expenditure. The old Ringsend Bottle Works over the way are now re-organised, and white glass bottles and jar making are going ahead. The old system of mouth blowing is not wholly discarded, as in cases of special and comparatively small orders it is more economical to manufacture by this method than by machine.

This Company has about five thousand customers. It supplies retailers as well as wholesalers and many of its customers have their names embossed on their bottles. We were glad to see such life and bustle about the place. The Company employ about 120 men, and sometimes the number goes up to about 200, and pay wages to the amount of about twenty-three thousand pounds a year-—a valuable industry.

This is a great insight into the company at this time and it is presented here in full including the comments on jam jars! It reinforces some of the points and observations made above. What is certainly of interest is the comment that stout was only bottled in half-pint bottles at this time, although there probably were exceptions, as has been stated already.

-o-

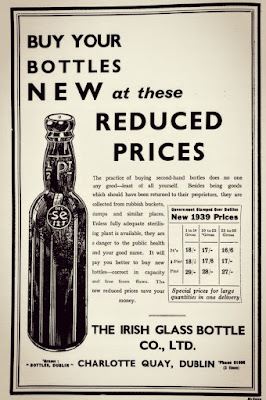

A helpful advertisement for The Irish Glass Bottle Company appeared in The Dublin Leader on Saturday 8th of July 1939 which shows a half pint bottle and encourages bottlers to use new bottles and not to recycle older ones – a far cry from the current ethos. It shows the prices of all of the legal beer bottle sizes and lists 1/3 pint bottles as ‘24’s’ which harks back to the older way of describing bottles by how many can be filled from a gallon. This size of bottle by the way was used for barley-wine and even for Guinness at one time, where they were called baby bottles - or even ‘Baby Guinness’ by our nearest neighbours, a name that means a different drink these days of course …

-o-

It is unclear precisely when this style of bottle with its ‘licence’ fell out of use but they were still being used in the 40s (The design and verification image were still being used in advertisements in 1944) and probably the 1950s – long after the term Saorstát Eireann was made redundant.

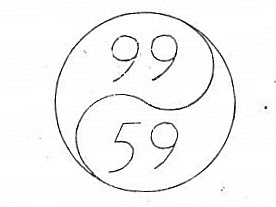

New regulations issued in 1958 introduced a new verification design and regulations for bottles that was to come into force on the first day of January 1959, and which revoked the older legislation. So this appears to be the end of this style of bottle verification and presumably these were replaced by plainer, less embossed bottles of similar shape, and the half-pint version appears to have lost its shoulders in favour of a sleeker look. These bottles presumably feature the new verification stamp, with the date below and the verification inspector or area above. But according to part 6 and 7 of these new regulations:

(1) The stamp of verification to be used at a licensed bottle factory shall be of the form and design prescribed for the purposes or Regulation 5 of these Regulations, save that it shall not be obligatory to include the figures indicating the year of stamping.

(2) Notwithstanding paragraph (1) of this Regulation, the stamp of verification used at a licensed bottle factory in pursuance of Regulation 6 of the Weights and Measures (Stamps) Regulations, 1928 (S. R. & O. No. 72 of 1928), may continue to be used at such factory.

This would appear to state that the bottle factories can continue to use the older style of verification but could change to the new style - without the date - if they wanted to, but it is unclear when exactly they completely disappeared from the pubs and grocers, although it’s probably fair to assume they were gone by the 1960s.

-o-

It is also unclear when exactly the pint bottle as a serving size began to gain more popularity in Ireland but it was possibly on the rise over this same later period driven by the abovementioned brands, and in 1976 Guinness changed from the old, shouldered bottle like the one shown above to the new rocket-shaped one we are familiar with today. The half pint bottle of Guinness sadly disappeared in 1995**, and all of this size of serve from the other breweries in Ireland were well gone by this stage, as were most of the breweries themselves and the many bottlers both large and small.

We can see that our love for a pint bottle of any beer is quite recent – or at least relatively so - but that pint bottle is still around, and hopefully will be for a while as a last vestige of a bygone industry and trade.

Liam K

* There is more on the subject of bottles here.

** The bottle change is feature in this post.