As you walk along Farren’s Quay in Cork, heading west towards North Mall it is usually necessary to stop at the busy junction where Shandon Street flows on to North Gate Bridge as it crosses the river Lee. While you wait patiently at the crossing for that little green person to appear, it’s difficult to miss the ghost of a sign - or in fact a ghost-upon-a-ghost of a sign - on a handsome brick building across the road. The words ‘Arnott’s Prize Medal Porter’ are still clearly legible in faded white paint on the first floor of number 64, framed in a plain cartouche and sitting nicely between two windows. This large object – and it can still be called an object, regardless of its size, make up and position – is the wraith like remains of an advertisement for a long-gone Irish beer and a pointer to what once was a brewery-tied public house, something that Cork – unique for Ireland – was famous for. Breweries and pubs in other cities did have similar arrangements, both official and unofficial, but not quite so many or with so obvious a tie. Being a tied-house meant that the public house was obliged to purchase beer from their tied-to breweries due to various factors such as the brewery owning the property, the license, or for services rendered or payments made, and it was of course a much more common practice in England.

-o-

Sir John Arnott, an M.P. and then Mayor of Cork purchased an old, existing brewery near St Fin Barre’s cathedral in Cork at the end of 1861 and by the following year was brewing both porters and ales. Arnott’s – or St. Fin Barre’s – brewery was in direct competition for the porter, and to some extent the ale, trade with Beamish & Crawford, Murphy’s and Lanes brewery who were all based in the city. As well as supplying their beer locally they were exporting to England, Scotland and Wales plus more exotic climes such as the Mediterranean and Barbados.. By the early 1880s Arnott’s were also operating a separate ale brewery in Riverstown just outside Cork city, and in 1882 at the Exhibition of Irish Arts and Manufactures held in Dublin the company was awarded medals for both its Porter and its ales. They entered their beers in The Cork Exhibition the following year and won medals for its pale ale but seemingly not for their mild ale, nor its porter - so it is probable that the prize that they were advertising in this painted sign was the one awarded in 1882 although it could relate to an even later award. (Incidentally, one judge criticised their pale ale at the Cork exhibition for being made with water that was over ‘Burtonised’ with mineral additions!) The company was wound up in 1901, just a few years after its founder died, and was purchased by one of its two main rivals, Murphy’s brewery, who bought both the porter and the ale brewery as well as the tied-houses. Murphy's promptly closed down the brewing side of the enterprise, and presumably started selling their own beers in the numerous Arnott tied houses that dotted the city. Curiously and perhaps sadly, when most people hear of Arnotts these days they would think of the department stores bearing that name, which were also part of sir John’s business empire, but for a not too short period at the end of the 19th century it was a relatively large concern, it was even visited and written about briefly by Alfred Barnard, who included and described it in one of his volumes on The Noted Breweries of Great Britain and Ireland, although not in the most exciting terms.

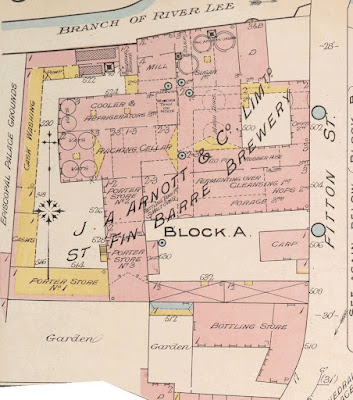

Below we can see a plan of the brewery as it was in 1897, roughly around the same time that the sign was painted on the wall of the public house and when Barnard visited. It shows its three porter stores and the general layout of the brewery in good detail, including a sugar tank which probably shows that they were using some sugar at least - which many Irish breweries did apart from some very notable exceptions - at this time in their brewing.

The sign on the then public house appears to have been painted sometime between 1882 and 1901, given the award date and the closing of the brewery, with the original fainter wording underneath possibly dating from closer to the earlier year and second closer to the latter date. During much of this period the public house at 64 Shandon Street was being licenced by a succession of women. Catherine Healy appears to have taken it over, possibly from a Thomas Healy, in 1889. A Norah O’Connell was running the business in 1896 when she changed the licence into her married name – Buckley. Julia O’Connell was named as the licensee in 1898 and then later than our period in 1908 it was being ran by an Ellen O’Connell. During the time up to 1901 it was tied to and therefore was supposed to sell only the beers supplied by Arnott’s brewery, but even after the breweries were closed by Murphy’s in 1901 the ghostly sign remained, getting slowly fainter over the decades but a nice reminder of Ireland’s brewing history for all to see.

-o-

But here’s an interestingly footnote. Arnott’s Prize Winning Porter returned briefly in 1997, as according to a snippet in a newspaper column from that year it was rebrewed in some form at least by Murphy’s for the release of the Ó Drisceoil’s book - The Murphy’s Story, which was published in that year. It appears to have been keg only and there were branded glasses issued bearing the name of the porter as well as that of the original brewery. Some of these glasses, and the occasional pump clip, are still to be spotted in pubs around the city of Cork if you know where to look …

Liam K