In July 1968 the Watney-Mann brewery group quietly test marketed a batch of Murphy’s draught stout brewed at The Lady’s Well Brewery in Cork on a target audience in 20 of their Manchester pubs.1 This soft launch must have been a relative success as it in turn led to a bigger campaign in June of 1969 when Watney-Mann were joined by Bass-Charrington - both giants of British brewing at the time - in trialling and marketing that same Irish stout in their pubs in the hope of unseating Guinness’s grip on the bar counters of Britain. Now under the guise of ‘Colonel Murphy,’ it was trialled in 500 of their pubs in Manchester and Brighton, with the hope of launching it in 8,000 pubs across the island in the future.2 The name change and choice seems a strange decision, as nitrogenated draught Murphys had just been launched in Ireland the previous year with attractive, trendy branding3. That new branding featured a modern and stylised version of their famous older image of the strongman Eugen Sandow holding up a horse with one hand, which would seem to have been a much more marketable image and story to use and push in Britain. (‘Colonel Murphy’ was presumably named after Lt. Co. John F. Murphy who was the last of the Murphy family to play a direct role in the brewery.)

-o-

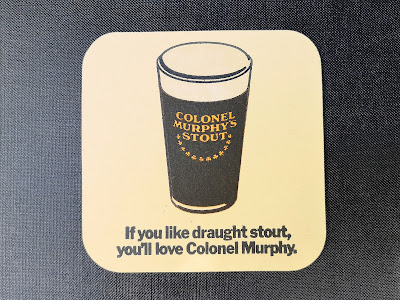

A newspaper campaign was launched in The Manchester Evening News over a period of months with the tagline we see on the beermat - ‘If you like draught stout, you’ll love Colonel Murphy’ - hardly the catchiest piece of wording and design ever produced.

The advertisement continues:

In their time, the Irish have produced two great draught stouts.

Colonel Murphy is the one you’ve never heard of before,

Because the Irish have kept it to themselves for the past 113 years.

Now at last it’s being shipped over from County Cork to England.

You won’t find it everywhere, but in many Watney-Wilson and

Bass-Charrington houses. And it’s worth looking for.

It’s dark, smooth and slightly bitter, with a grand creamy head.

A noble drink, if ever there was one.

There are obvious issues with this wording such as the comment that there have only been ‘two great stouts’ produced in Ireland - Beamish & Crawford might disagree for starters, although their stout production was in a state of turmoil at this time - and the implication that Murphy’s never exported stout to England in the past. (They had, and they have done so since too of course.) However, we know from experience that beer marketeers are not the most reliable source, or communicators, of Irish brewing history. ‘Watney-Wilson’ appears to have been referencing the Wilson group of pubs that Watney-Mann had taken over in the early 1960s and who had a considerable number of pubs in Manchester, hence the name use here which would have resonated more with local drinkers presumably.4

At the end of August a full page advertisement appeared in the same paper that listed every pub in Manchester and the surrounding area that was stocking Colonel Murphy, a list that ran to 347 different establishments.5 The following month in a half page advert under the title ‘England’s Gain’ the marketing was still focusing on its Irish origin saying that ‘naturally enough the Irish are sad to see it go. It’s dark, smooth and bitter with a grand creamy head. A drink fit for heroes.’ It also played with the exclusivity of the beer by saying, ‘It’s here. Not everywhere. But in many Watney-Wilson and Bass-Charrington houses. Try it.’ So it would appear that the brewing companies were putting a relatively sizable marketing budget behind the launch, albeit just at local level.6

-o-

Similarly themed adverts ran through October of 1969 but alas it was a short-lived experiment, and commenting on the pulling of the brand from its pubs a spokesperson for Bass-Charrington said in a newspaper report in November that ‘it would have cost too much to get [it] off the ground nationally’ so they had decided that ‘if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em’ and that both brewing companies would be selling Guinness in their pubs within 12 months. It also quoted a ‘jubilant’ Guinness spokesperson who said that ‘it was the biggest challenge yet to draught Guinness and the fact that these great companies failed will discourage others.’3

Another report regarding Guinness draught’s success in the English market also discussed Colonel Murphy’s demise while noting that both Watney-Mann and Bass-Charrington had breweries in Cork, with the former owning Murphy’s (Lady’s Well Brewery) having acquired 51% of the shares in 19673, while the latter controlled Beamish & Crawford, both of which were running below profitable capacity, and the hope was that Murphy’s Stout - albeit under a different name in Britain - would change the fortunes of that brewery if the experiment was a success. The article goes on to say that they might have been unlucky with their timing, as it had been ‘a hot summer for their test marketing’ but as it was still on sale up until early winter it’s hard to put much fate in that comment. The reporter also makes the point that ‘the Bass end of Bass Charrington has taken draught Guinness for some time’ so it appears that some of its pubs were already selling it at this time if it wasn't a comment on an older historical connection.7 The chairman of Watney-Mann, Peter Crossman, also stated in 1970's The Brewing Trade Review that ‘although we had an excellent beer which achieved reasonable sales levels, the investment and effort required to catch up with the public awareness of draught Guinness would have been less profitable to the group than the sale of a product already marketed.’

It is worth noting that at this time approximately 30,000 drinking establishments in Britain were selling draught Guinness and that figure was growing at a rate of 25% per annum,8 but this still seems a strange decision given their abovementioned involvement and investment in The Lady’s Well Brewery which brewed the stout, but perhaps it was a sign of them losing their love for Cork and Ireland despite those adverts they commissioned, where they sang the praises of Colonel Murphy, and indeed by the summer of 1971 they had severed their ties with the brewery and sold their stake in it.

-o-

Very little breweriana seems to have survived of Murphy’s English adventure, but there are - as we can see - some beer mats and there are probably some nice conical pint glasses sitting on the back of a few English collectors’ shelves, but it’s nice to know that at the end of the sixties a Cork brewed stout almost put it up to the biggest player in the stout market in Britain.

It's interesting to think what might have happened if they had succeeded …

Liam K

* Apart from irksome use of ‘Eire,' surely most of the draught Guinness drank in Britain was produced in their brewery at Park Royal in London?

Please note, all written content and the research involved in publishing it here is my own unless otherwise stated and cannot be reproduced elsewhere without permission, full credit to its sources, and a link back to this post. The attached image is the author's own and cannot be used elsewhere without the author's permission. Newspaper research was thanks to The British Newspaper Archive and other sources are as credited.

1 The Manchester Evening News - Tuesday 2nd of July 1968

2 The Daily Mirror - Tuesday 11th of November 1969

3 The Murphy's Story - The History of Lady's Well Brewery, Cork by Diarmuid Ó Drisceoil and Donal Ó Drisceoil

4 The Manchester Evening News - Friday 1st of August 1969

5 The Manchester Evening News - Wednesday 20th of August 1969

6 The Manchester Evening News - Thursday 11th of September 1969

7 The Birmingham Daily Post - Tuesday 11th of November 1969

8 The Daily Mirror - Tuesday 11th of November 1969

I had often wondered when the other stout breweries switched to nitrokeg, so I'm grateful to learn that it was 1968 for Murphy's. I guess this was after their campaign making a virtue of the old-fashioned dispense failed: "Murphy's from the wood, that's good".

ReplyDeleteAs far as I'm aware, Park Royal mainly supplied southern Britain with Guinness. For the north it was still shipped across from Dublin, so it is possible that more came from James's Gate than London.

And irksome and all that it is, the misspelled "Eire" does have some legal precedent, being the name given to the State by British Law in 1938 under the Eire (Confirmation of Agreements) Act. It had been changed again with the 1949 Ireland Act but I can see how it stuck in popular consciousness, with everyone hooked to the international news during the war.

Cheers for all of that!

DeleteWhatever about the legality of the term, "Eire" is spelt incorrectly. Éire is the name of the island; eire means something else entirely.

DeleteI'm more forgiving of its misspelling than its use, although TBN has but some clarification to that, given the timing. Still being used by people now mind you!

DeleteBack then they wouldn’t have had accent marks on type writers in the UK.

DeleteIt is great to see stout being served in conical glasses a history that has been erased by BMG and drinkers alike in Ireland.

What was going on with Beamish stout production in 1968?

Oscar

http://beerfoodtravel.blogspot.com/2020/01/tower-stout-beamishs-rebrand.html

Delete