Merrie England in the Olden Time by George Daniel (Bentley's Miscellany, Volume 7 - J. M. Mason, 1841)

There is probably no piece of vintage, beer-related glassware that is talked about in the same reverential tone as the Guinness Waterford tankard. For many collectors of breweriana finding an absolutely perfect example is akin to discovering The Holy Grail, and almost as hard to acquire. Even those who show indifference to Guinness itself have a fondness for the barrel-like shape, the curvaceous handle, and that gold lettering with the harp sitting above. It has, for many at least, a deserved iconic status in Irish - and British - beer history, much more so than the relatively recent interloper that comes in the shape of the tulip pint glass.

Admittedly, the quotation above by George Daniel is a little out of kilter with the timeline, material and origins of the beer-related item we are focussing on here but it is an evocative piece of prose and poetry in honour of a tankard of stout. The wonderfully described ‘cauliflower-wigged’ and ‘foaming’ description of the head on the vessel in that piece is at odds with how we see draught stout’s image now, but it might be viewed by some as a better manifestation and a more inviting portrayal of that drink than the sterile, domed band of nitrogenated bubbles to which we have become accustomed these days.

-o-

Although our tankard was indeed made in Waterford it is not strictly speaking the ‘Waterford Glass’ that is world renowned for its quality, substance, and appeal, but rather a different quality of product that was being made by the company for domestic and bar use from when the firm started producing glass in Ballytruckle just outside Waterford in 1947. The material used for these items was soda glass which contains no lead or potash as opposed to the crystal glass that the company is well known for producing. This type of glass was being made right up until 1970 in the company’s plant at Johnstown - where they had moved to - in the centre of the city, and was still being sold for a number of years after that. As well as Guinness tankards the company also produced branded glasses for many other drinks such as Carling Black Label, Idea, Harp, Carlsberg1 and probably Time, Smithwicks, Phoenix, Double Diamond, Celebration and many others. Interestingly, they also produced another iconic piece of glassware, the stemmed glass for Irish Coffee with the gold band on top and a shamrock on the flattened section of the stem, which were exported to North America in large quantities1 These, along with the barware and the many lines just for domestic use, meant that the Waterford Glass Company were quite a prolific maker of daily-use glassware as well as high-end lead crystal. It is probably fair to say that almost every Irish household of a certain vintage has a piece of ‘Waterford Glass’ in a cupboard or on a shelf, although most owners would not recognise those pieces as such.

Many of these lines were stickered with a rectangular label on their base with the words ‘Waterford Domestic – Made in the Republic of Ireland’ or a lozenge shaped one in silver and black with 'Waterford Barware - Made in the Republic of Ireland.' Those stickers are obviously now quite rare on any glasses used in the pub trade but some examples still exist with the label in place and intact.

Without some insider knowledge of the company's process of making all of these glasses we can only speculate as to how exactly they were created, but they appear to have been mould-blown by mouth rather than by machine and then, in the cases of tankards, the handles were dropped on and shaped by hand afterwards. This would seem to be the most efficient way of producing such a large quantity of relatively uniform products in a cost-effective way - but this is mostly speculation.

-o-

Glass tankards were quite a rare thing in Irish pubs in any part of our history up until the 1960s, with pewter mugs and fluted or plain conical pint glasses (tumblers as they were often called) being used up to that time along with Noniks with their pronounced bump near the top of the glass. In England certainly, and perhaps the rest of Britain, glass tankards were much more in use regionally at least, with dimpled mugs and multi-faceted tankards being relatively popular up to this period. This may be the reason why Guinness decided to launch this style of glass for its new Draught Guinness once they had ironed out any issues with the Easi-Serve dispense of their new stout and were viewing a campaign to install the new system in as many pubs as they could on these islands. Our near neighbours were huge consumers of Guinness in various forms, and the London brewery at Park Royal was in full swing so it would make sense that decisions were made based on that market rather than the Irish one.

The tankards weren’t used at the initial launch of Draught Guinness in 1961 but appear to have been rolled out sometime after 1963, and there are certainly surviving Irish examples of the glasses with verification marks for that year. In fact, early in Draught Guinness’s launch in England it was advertised in dimple mugs, a thought which would horrify and perplex many of today’s most militant Guinness drinkers!

Alan Wood, who took up the position of Guinness Advertising Manager in Britain in 1961 states in an undated note in ‘The Guinness Book of Guinness’ that the tankards ‘just happened’ and were part of that Draught Guinness roll-out ‘throughout Britain’ – and presumably Ireland around the same time. He also implies that the Waterford Glass Company were looking for a line that they could relatively easily produce, which they could use as a starting point to expand into this type of branded, bespoke barware product, and something that would also help with training and apprenticeships. The discussion between the two companies focussed on a lightweight, ‘generous’ looking tankard that would show-off the aesthetics of the beer, and that had a ‘quality feel’ that would suit a pint which would be a little more expensive than the norm. Waterford Glass came up with the design and at a price that very much suited Guinness’s budget. Interestingly, Mr. Wood says in the same note that ‘hundreds of thousands’ were produced and possibly a million!2 (There are currently no figures available as to how many were actually produced although the appear to have been packed in boxes of six, and if every pub on these islands received a box or two then the numbers would soon add up ...)

The golden logo applied to the tankards comes in at least two variants, the first being the lettering that had been around for decades with slight changes up until sometime in the mid-sixties when the company changed to the second version, the Hobbs or Hobbs-face stencil-like font with gaps in the narrow points of the letters. (This was first used in 1963 on posters and named after Bruce Hobbs at the SH Benson advertising company, who was allegedly inspired by street signs in Paris and the crude stencilled lettering on hop sacks.3) The earlier font also seems to have a less commonly seen version of the harp logo which differs a lot from the more ornate versions seen on bottle labels and was possibly for ease of printing, although it was replaced by a lightly simplified version on the later glasses and elsewhere. Also of note is that on some earlier versions of the half pint glass the logo faces a right-handed drinker whereas it usually points outward and away from them - and should do from a marketing standpoint on any glass. The tankards came in pint and half pint sizes, as well as a smaller run of three-pint versions for use as displays in pubs. These have become the real Holy Grail of Holy Grails for collectors and feature the word ‘Draught’ above ‘Guinness’ in the early letter and logo style.

In print, the glasses appear to have been first used in advertising Draught Guinness on posters in Ireland in 19633 and in newspapers in this country by the following year. They first appeared in Britain on advertising posters in 1966 /1967, when ‘the tankard was adopted as the symbol’ for the product.4 (Those advertisements also feature the ‘older’ style typeface, which appears to change around the end of the decade to the newer version, as mentioned above.) The tankard falls out of favour with marketing companies around 1980 and rarely appears after that, replaced by the conical glass for a while and then the aforementioned tulip pint glass we are now very familiar with from advertisements and social media.

Verification marks seem to have been applied around the time that the glasses were originally made and before the logo was applied, this can lead to errors and confusion in dating certain glasses. For example there is an officially verified tankard from 1969 which has the logo for Cork city’s 800-year anniversary in 1985 on the side of the glass. Curiously, this version has the Guinness logo on both sides, which wasn’t a common practice and these may have just been commemorative gifts. If it was used in pubs then this Cork version helps to show how long these tankards lasted in the trade, which would have been about two decades. It should be noted that these tankards weren’t universally used for draught Guinness on these islands, as many publicans used some of the more ‘normal’ styles of practical glassware instead or as well.

The design may have been an excellent conception and these glasses were relatively tough but they were notorious for cracking and breaking at their Achilles' Heel where the handle meets the top of the glass - a fault often seen on specimens found for sale today. They were not really suitable for the modern pub – not to mention how unkind dishwashing machines were to gold lettering – so it is unlikely that the publican's who used them mourned their passing, although many have revived or remade the old red Guinness lightbox tap fronts that carries their image, while serving the beer in curvaceous but unhandled pint glasses just to add insult to injury.

Many also disappeared out of pubs by way of theft. In 1978 in Lincolnshire in England two ladies were convicted and fined £25 each for stealing two ‘special and distinctive [half-pint] Guinness mugs’ from a pub having been reported to the authorities by the publican – both women admitted to ‘taking the glasses worth £1.20, out of the pub in their handbags’ according to a local paper. It appears from this that Guinness charged the publican £1.20 for a half-pint tankard.

-o-

There were other, later versions of this Guinness tankard too. A pressed glass edition was available from probably the 1980s with gold or beige lettering and it can be easily identified by its flattened, moulded handle as distinct from the hand-added, rounded handle on the originals. German glass producers Sahm also produced a 400ml similar tankard with the Hobbs typeface in gold in the 1970s. There was also a French-made half pint version with a more rounded handle5, and Viners of Sheffield produced an attractive pewter version too, both of these are probably also from the seventies.

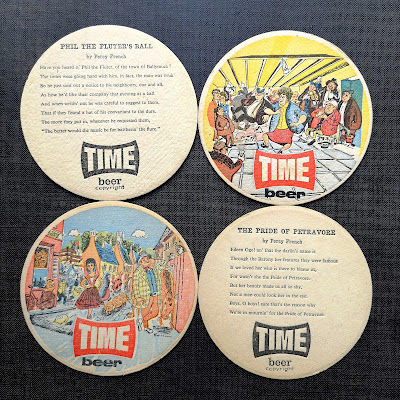

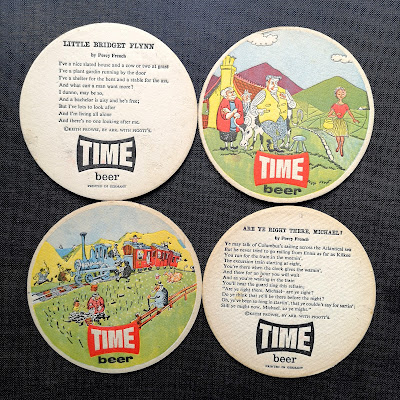

After the Guinness tankard was launched it opened the gates for almost every other Irish brand of beer and soon tankards were everywhere in pubs in Ireland in the sixties and early seventies. Time, Smithwicks, Double Diamond, Phoenix, Carling Black Label, Celebration, Bass, Watney’s Red Barrell and Macardles all had glass tankards of various types and designs, many made by the Waterford Glass Company as mentioned above. The Harp tankard, in its second or third version, was the last to be used in pubs, probably in the mid-nineties and long after the other brands had disappeared - or their tankards had at least - or changed to something less cumbersome to suit a changing drinker. [EDIT: The Franciscan Well Brewery were using a branded glass tankard for their beer up until quite recently, and possibly still do - thanks to Keith @j_k357 on Twitter.) Unbranded glass tankards were also used in Irish public houses for a time, before finally falling out of favour in the late nineties apart from the occasional hold-out like J & K Walsh in Waterford who were using a tankard for Guinness and other beers up until relatively recently.

-o-

Perhaps the glass tankard is due a revival here in Ireland? Maybe an enterprising microbrewery will include one in their selection of beer glasses?

So hopefully one day soon we can pour a proper stout into a branded glass tankard again to create that cauliflower-wigged stout, and raise that foaming tankard high …

So say I!

Liam K

1Waterford Crystal – The Creation of a Global Brand, 1700-2009 by John M. Hearne

2 The Guinness Book of Guinness 1935-1985 edited by Edward Guinness

3 The Book of Guinness Advertising by Brian Sibley

4 The Book of Guinness Advertising by Jim Davies

5 The Guinness Archive Online Collection